Drive through just about any traffic circle in Lima, Peru, and you will likely see a female police officer directing traffic. Dressed in neatly pressed, dark green, buttoned uniforms and helmets, this newest segment of the National Police of Peru (PNP) is the friendly public face of the country’s policing for thousands of Peruvians—and not just because they are helping lost pedestrians and motorists and keeping order on Lima’s car-choked streets.

The women officers represent the front line in a government effort to revive confidence in law enforcement in a country known for rampant corruption. The fact that they are women is no coincidence: officials (and the general public) believe they are less corruptible than men.

Are they right?

The female force dates back to 1998, after studies commissioned by the World Bank and other international organizations during President Alberto Fujimori’s government (1990–2000) concluded that female police officers were more honest, disciplined, hardworking, and trustworthy than their male counterparts.1 Ranking PNP officers agreed. Commander Pedro Montoya, who was then training an all-female motorcycle brigade, said it was “undeniable” that women were more honest.2

By 2009, the “feminization” of the transit police throughout Peru—where each transit division falls under a regional commander—had transformed the nation’s law enforcement. Today, 11 percent of the PNP’s police officers are women. And, significantly, of the 2,500 transit cops in Lima—including both oficiales, or officials and administrators, and suboficiales, or rank-and-file members—93 percent are female.3 José Abelardo Alvarado Alegre, director of the transit force, says he is happy with the results, since female officers are “more harsh at giving tickets, strict and difficult to bribe.”4

Until recently, there has been no way of measuring the success of the PNP’s initiative. But in 2010, I received permission from the PNP to study the experiences of female transit officers and to be the first researcher to interview them. My study looked at the careers of 40 women through seven focus groups, and surveyed more than 400 females in Lima’s eight transit units. However, the PNP only authorized interviews with rank-and-file officers and not those in administrative posts. Lima Mayor Susana Villarán and Colonel Alvarado Alegre were also interviewed for the study.

The findings show that women believe they have reduced corruption. But they also believe that corruption remains the most pressing problem within the PNP. The perceived decrease in corruption is not universally shared among women. Clear differences emerged based on career and family circumstances. In fact, while having family in the PNP and access to on-the-job training predict overall higher job satisfaction, these variables do not lead to a female officer having a more favorable estimation of improvements in the integrity of the PNP.

Similarly, the barriers to moving up the career ladder beyond the transit division and other unresolved gender-related problems might be undercutting women’s original resolve to fight corruption. Although other countries have adopted police reforms similar to those of Peru, policymakers should be cautious in rolling out female police units until Peru’s model can be proven to have reduced corruption while satisfying the specific needs of women officers.

Battling Corruption

Corruption is an accepted part of daily life in Peru, and any taxi driver will lament that paying coimas (bribes) to police is part of the job.

The numbers agree. A 2009 government report found that 11,876 public servants had been accused of corruption-related charges since 2002.5 And a 2005 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research concluded that the PNP is the second most corrupt institution in the country (the judicial system ranks first). That same year, another report suggested that the deep, embedded culture of corruption at the PNP begins at the top.6 Even with these dismal rankings, the same taxi drivers who bear the brunt of daily corruption seem to concur that the feminization of the transit division has been successful. One taxista summed it up: “We all know that you can’t bribe women.”

Some policewomen have said that taking money from male drivers feels a lot like prostitution.7 “We were hired to clean up the streets and we have done so. Drivers may insult us, but they don’t offer bribes,” said a female transit officer who asked to remain anonymous.

In fact, 95 percent of women surveyed for the study agreed that female transit officers have helped to reduce corruption. That statistic is corroborated by the 67 percent who think that women are less corrupt than men and the 87 percent who say that women are stricter than men.

The public agrees. A 2004 opinion poll conducted by Apoyo Opinión y Mercado found 86 percent approval for female transit officers’ work.8 Nevertheless, the female police surveyed identified corruption as the PNP’s biggest problem. While low-level corruption may have been “cleaned up,” the women in the focus groups noted continued high-level corruption.

The challenge is that institutional corruption is often hidden from the public view, but corruption on the streets is extremely visible and tarnishes the image of the PNP. “Maybe 1 percent of women take bribes, but when one female takes a bribe, we are all denounced as corrupt, when the real corrupt ones are our supervisors,” said another female transit officer who asked to remain unidentified.

Stuck in Transit

The prospect for women moving into supervisory posts—and cleaning up such top-level corruption—is not encouraging. According to Col. Alvarado, only 100 female officers have been promoted to the administrator level. So female traffic police may be changing the public face of the PNP, but they are being shut out from making a larger impact.

A police reform investigation in the early 2000s confirmed this challenge. It found high-level corruption in three main areas of PNP activities: the pension system; gasoline procurement and distribution; and medical and housing benefits. Attempts to find solutions to these problems met little success; reforms ran in direct contrast to the vested interests of high-ranking senior officials.9

Still, is being female the key determining factor in the incidence of corruption? Women see themselves as less corrupt than men and as having positively improved the image of the police. But opinions about their job and productivity are directly tied to access to on-the-job training and career mobility. When those are lacking, it may affect not only their job satisfaction but also their willingness to clamp down on corruption.

Judith, a suboficial officer who has worked for the PNP for eight years, is a typical transit officer frustrated with her position.10 A job with the PNP originally seemed like a great opportunity, as she would be able to follow in the footsteps of her uncle. But Judith is bored with her job and a male-dominated culture that offers few opportunities for career growth. “I used to have pride in my job for being a woman,” she said, “but the PNP doesn’t give women opportunities to rise up.” Judith is now only on the force to support her child; otherwise she would quit.

Like many others, Judith complained that the ability to participate in advanced training and move into other areas of policing—opportunities that are supposed to extend to all PNP officers—are limited. For example, women must pay expenses and receive permission from their superiors to enroll in a course. One common lament heard in focus groups: “I always wanted to get more training, but didn’t have the money to pay.” And even when women in transit are permitted to take training classes in areas like driving a motorcycle or criminology, training does not guarantee a promotion. Even after passing an exam at the end of training, they are only eligible to move to another division with permission from superiors. That is the story of Catelina, who has reached the pinnacle of her career as a PNP officer. She performed well on a standard knowledge test and was recommended for additional training by her superiors. Now, at age 29, she has the dream job: one of two personal bodyguards for U.S. Ambassador to Peru Rose Likins—a PNP post specifically reserved for women. Like almost all female police academy graduates, Catelina started her career in the transit division. She then worked in drug enforcement and police stations before finding her home at the embassy. Unfortunately, most women’s stories are more similar to Judith’s than to Catelina’s.

Another set of women who believe they have positively changed the image of the police includes those with more experience in the PNP. But more time on the job also correlates with lower levels of job satisfaction.

Norma was hired in 2000 and said that at the time of the reform “women held immense pride in their jobs because they were hired to do something men could not.” She said most women felt a strong sense of mission. Their collective pride was often voiced in focus groups, boasting, “We were hired to clean up the image of the police” and “the public trusts women more than men.” But their survey responses also show frustration due to lower pay and fewer opportunities for promotion.

In contrast, policewomen with fewer years of experience are less focused on reducing corruption and improving the PNP’s image. They tend to view transit jobs as a means to an end, a “trampoline for other jobs” in the words of some focus group members. Susana, for example, had just recently entered the PNP from the academy, but has no desire to work in transit: “I want to leave [transit] as soon as possible and am saving up so that I can become a lawyer.”

Like Susana, almost every female police officer graduating from the suboficial police academy is initially placed in the transit division without regard for her career preferences. As a male squadron leader pointed out, “Women must prove themselves for 5 to 10 years in the transit division before they are placed in a different division.”

In interviews, most women stressed that they desperately wanted to leave transit. Still, the average female transit officer spends 81 percent of her career in the transit division, and more than half of transit policewomen have never worked outside the division.

Women and Transit Roles

One problem in getting women out of transit is that most see themselves as better than men at carrying out some of the traditional roles of a transit officer. Most women, for example, think they are better than men at giving tickets. A female suboficial commented, “When we put on a uniform, it means that we were hired to do a particular job: enforce traffic laws. But outside the uniform, we are women, wives and mothers.”

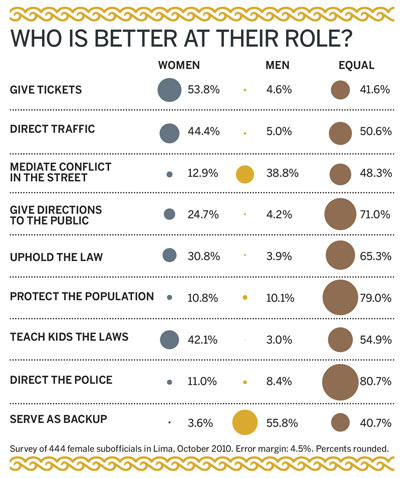

Furthermore, according to surveys I conducted with female officers, women believe they can perform as well as men in roles that are traditionally assumed to be male: enforcing the law, protecting the public, mediating conflict, or directing the police.11 [see table on p.45] Still, even though male and female officers are capable of performing the same tasks, women face an added challenge of having to deal with certain “gendered” problems within the PNP.

Respondents identified an inflexible work schedule (women work more than 12 hours per day), low pay and the double role of being a mother and policewoman as the top problems. Additionally, many women mentioned tension between female officials and suboficiales, discrimination against women, abuse, and favoring “pretty” women.

The PNP is just beginning to address the new issues created by the inclusion of women. For example, the arbitrary dismissal of women due to pregnancy was prohibited only five years ago.

Over the long run, the question is whether the PNP will address such “gendered” problems that accompany the feminization of the police force. For one, attitudes toward women need to change. The director of the transit division asserted that the inclusion of women was “good on one hand and bad on another because of women getting married and having children, which both cause problems in the daily operations.”

Needed PNP Reforms

At present, there is rising dissatisfaction among female transit officers. It seems that the original pride in being corruption-busters wears off with time, as younger female officers are looking for other opportunities and are more vocal about problems. The question then is what to do.

Female suboficiales who participated in this study suggested that improving women’s incorporation into the PNP should include adopting alternative scheduling models; creating family benefits such as maternity/paternity leave; addressing women’s health and safety concerns; increasing pay to match performance; integrating the suboficial and oficial branches; creating an internal ombudswoman who has the power to report and punish abuse and discrimination; and establishing an internal counseling program. Declining morale in the female force means that if these suggestions are not taken seriously, the PNP may backslide from its achievements of the past few years.

Catelina is one of the PNP’s notable success stories because she was able to transition out of the transit division and receive a prestigious post in the PNP. But Judith illustrates that not all female officers can rise in their career.

Peru is still far from mainstreaming gender in its police force. The incorporation of women to reduce the image of corruption is only a first step and its success in combating institutional-level corruption is yet to be proven.

At the same time, other countries have adopted similar models of including women in the transit division to reduce corruption. Immediately after Peru in 1998, Mexico City announced a reform to replace 900 male transit officers with women. El Salvador, Panama, Ecuador, and Bolivia have also included women in their transit divisions, though not as thoroughly as Peru. Other countries have taken the same steps but advanced farther. Nicaragua and Chile have much higher female participation rates in more diverse divisions, and Brazil has recently increased the number of women in administrative posts. Peru could learn from these examples.

Corruption will not be fixed merely by adding female officers. While there may be a reduction in street-level corruption through the inclusion of women in the transit police, administrative corruption and gender-based job dissatisfaction may threaten to undermine those gains. If the reforms are to do more than just change the gender balance on the front lines of the police service and actually improve the integrity of and respect for the force, the government will have to aggressively seek the full integration of women into the force.

ENDNOTES:

1. Jones, Patrice, Chicago Tribune, “To fight Corruption, Peru Turns to Female Cops The Theory: They Wont Take Bribes. April 23, 2000 http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2000-04-23/news/0004230200_1_young-women-male-traffic-women-police-officers

2. “Peru’s Women Cleaning Up Traffic, Chaos, Corruption, CNN August 21, 1998 < http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/peru/policewomen.htm>

3. La Mujer en Las Instituciones Armadas y Policias en America Latina: una aproximacion de genero a las operaciones de paz, Proyecto de GPSF No. 07-184

4. “Solo Las Mujeres Policías Dirigirían Transito en Lima,” El Comercio February 28, 2010

5. http://www.peruviantimes.com/02/peru-government-announces-creation-of-anti-corruption-commission/4745/

6. Gino Costa, Rachel Neild, “Police Reform in Peru” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, August 2005

7. “Peru’s Women Cleaning Up Traffic, Chaos, Corruption, CNN August 21, 1998 < http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/peru/policewomen.htm>

8. “Solo Las Mujeres Policías Dirigirían Transito en Lima,” El Comercio, February 28, 2009

9. Gino Costa, Rachel Neild, “Police Reform in Peru” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, August 2005

10. All names in the study have been changed at the request of the female officers.

11. Balkin, J. (1988) Why policemen don’t like policewomen. Journal of Police Science and Administration 16 29-38.